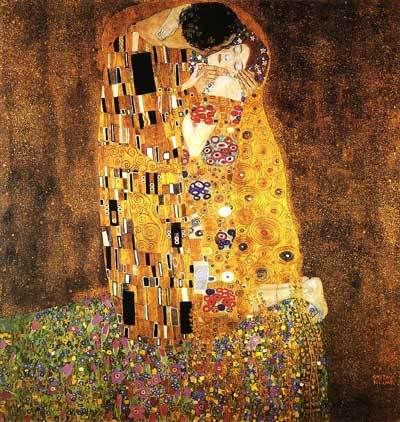

The Kiss (1907-08)

Even if you think you’re unfamiliar with the work of Gustav Klimt, if you’ve spent any notable amount of time in a dorm that houses college age women, you’ve likely seen at least one of his paintings, indeed his most famous, The Kiss. Posters of this particular work are ubiquitous in the domestic collegiate arena, and young women seem to hold a particular affinity for it. And I’m sorry if that sounds sexist, but it is a romantic painting, the sort of thing a certain cross section of young women are apt to appreciate, and I doubt that the majority of them are full-blown Klimt enthusiasts, given the dark and frequently male sexual dynamic of a lot of his work.

The Kiss depicts a man and woman kneeling on a bed of flowers. Their bodies are pressed tightly together under blankets that envelope them. He holds her head in his hands as she bends it back to allow his lips access to her cheek. One of her hands clasps his while the other lays draped over the back of his neck. Her calves can be seen protruding from under her blanket and her feet stick out past the flowerbed, which ends at a place that almost seems to drop off into the void.

Klimt was a big fan of ornamentation, and each blanket is covered in its own particular symbol, long, shaft-like blocks on his, circular figures on hers. (Decidedly unsubtle in this post-post-post-Freudian world, but bear in mind that Freud himself was only just beginning to simmer his theories at the time this was painted, in the very same city no less.) Through the way her blanket lies you can see a clear indication of her body, and yet at the same time the very fact that his blanket melds right into hers, coupled with what little of their actual bodies are exposed, come together to suggest that they are united as one entity, an important factor in the painting’s inherent romanticism.

Some find a theme of male domination in the work: his grasp on her, his position somewhat looming above her, the slightly phallic aura that caps their heads. But to me the peaceful, pleasurable look on her face belies any negative connotation of this variety. Klimt’s portrayal of the female face was ever expressive (as opposed to his depiction of men, whose faces, except in specific portraits, tended to be turned away from the viewer), and in this piece, and even more so in Danae, painted around the same time, he achieves a mystical sense of sexual ecstasy that almost seems to suggest sleep, and subsequently dreaming.

Next: Danae (1907-08)

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home