The Faculty Paintings

Much of Klimt’s early success was centered around commissions to create work that was not just to be exhibited but to become a part of public life, such as his depictions of ancient forms that were installed above the doorways of Vienna’s premiere art museum. In this vein, the Ministry of Education commissioned him and his business partner Franz Matsch to paint what came to be known as The Faculty Paintings, which were to be placed on the ceiling in the Ministry’s great hall. The three that Klimt was assigned, Philosophy, Medicine, and Jurisprudence, were expected to be celebrations of the achievement of rationality in the modern world. This was not, however, what the artist delivered, and the controversy stirred up by them ended with Klimt buying the paintings back from the government and renouncing any further state patronage. Many years later, the paintings were stolen by the Nazis. They were eventually destroyed at the end of World War II, along with other works, in a fire at Immendorf Palace set by retreating SS troops. I can only imagine what it would have been like to see these paintings in the flesh, so to speak, as their enigmatic quality, reduced as it is by the necessity of viewing them in the photos that survive, still has the power to provoke chills.

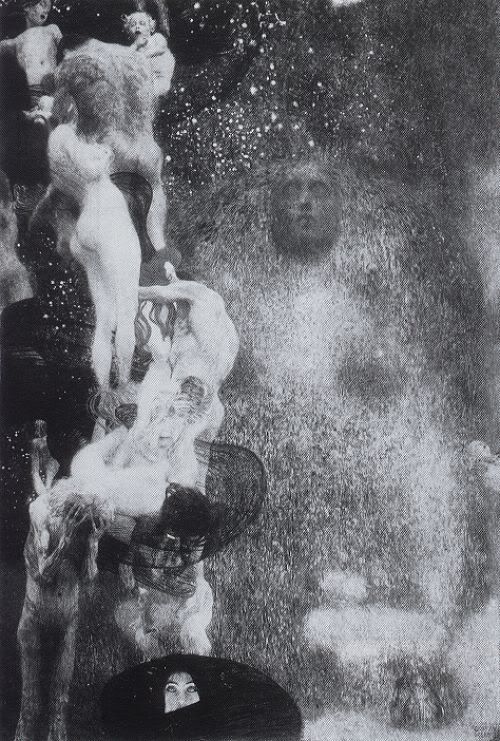

Philosophy (1907)

Klimt advocated a school of thought that emphasized the idea that, regardless of man’s copious achievements in terms of science, intellect, etc., he was still subject to nature’s whims. (I may be presenting that somewhat simplistically, but that was the gist. It is tempting to wonder how well-known his belief in this viewpoint was; his status as Vienna’s most revered artist notwithstanding, surely the Ministry would have been reluctant to hire someone who was prone to undermining the “light conquers darkness” sort of portrayal they wanted.)

Klimt portrays humanity as a column of bodies. While they display such common human traits as passion and despair, none of them seem to be in control of their destinies. They merely float through the universal ether, out of the darkness of which looms a sphinx, whose sleeping face is indifferent to them, much like the universal mysteries it represents. At the bottom of the painting, a solitary woman’s face peeks out from behind a cloak, her eyes peering out at the viewer as a lone indication of human sentience.

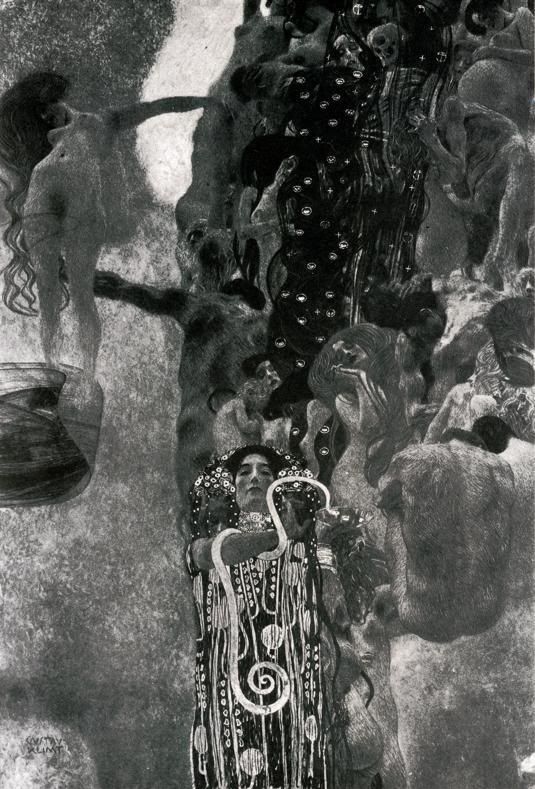

Medicine (1907)

Medicine shares a number of traits with Philosophy. Once again, humanity is represented as a floating column of bodies, though this one clearly illustrates various stages of life (including a skeletal death), most represented by women. Instead of Philosophy’s sphinx, we get Hygeia, daughter of Asclepius, granddaughter of Apollo, Greek mythology’s Florence Nightingale. She performs a ritual task, but is as indifferent to the nearby humans as the Sphinx was. And, like the solitary woman in Philosophy, we have one figure to the left, suspended in space, a baby at her feet, her arms thrown out in a display of vitality.

The nudity in Medicine caused a bit of furor, but it was nothing compared to the anger directed at Klimt by the city’s physicians. The artist’s representation of man’s journey and the ambiguous importance of the symbol of medicine was not the celebration of the healing arts that they had expected. But if the city elders had hoped the experience had taught him some kind of lesson, his third Faculty Painting would prove otherwise.

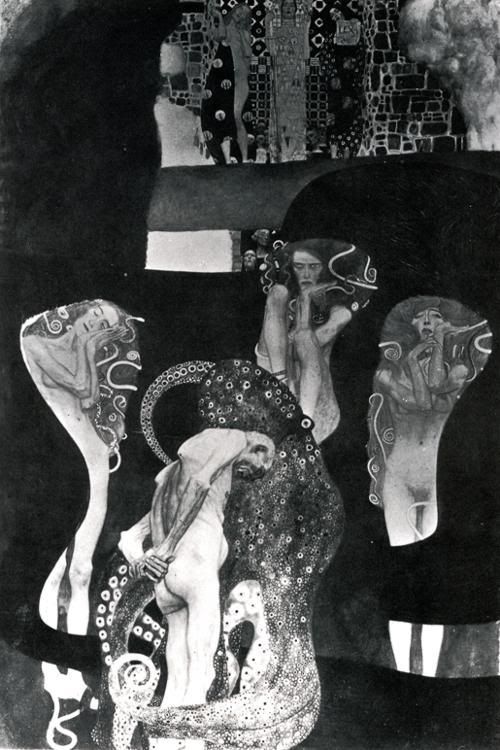

Jurisprudence (1907)

It has been speculated, but can’t be conclusively proven, that Klimt changed his original plans for Jurisprudence in light of the trouble the first two paintings had caused him. The picture shows a spindly, naked man, bound and placed within the confines of an octopus’s tentacles (I’ve always felt that the octopus was deliberately made to look like the sort of courtroom box in which a prisoner might have been confined). Before him stand the three Furies, and far above them, surrounded by judgmental, disembodied heads, are depictions of Truth, Justice and Law.

There are two popular interpretations of the painting. One goes directly to the idea that Klimt felt persecuted for his previous work (some believe the man is a self-portrait), and the other posits it as a metaphor of sexual shame. Certainly the Furies, who give off an air of both sexuality and malevolence, would seem to support the latter, as could the man’s posture, bending as he does in what could be considered guilt. Regardless, the fact that the lofty ideas of jurisprudence are far removed from the individual and the arbiters of his punishment speaks quite loudly. Here Klimt has moved from depicting the main theme of the painting as indifferent to man to making it downright hostile.

Next: a bevy of water maidens (1889 through 1907)

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home