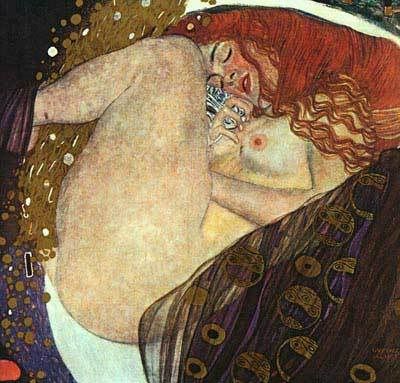

Danae (1907-08)

Greek mythology has a lot to offer modern civilization, including acting as a primer for any swinging gadabouts (godabouts?) who’ve split Mount Olympus and are looking to score with some mortal chicks. Klimt depicted two such happenings, including this painting of Zeus having his way with Danae in the form of a shower of gold. This, of course, is the beginning of the story of Perseus, but that doesn’t concern us right now. In fact, Klimt places us so firmly in the moment that the rest of the story might as well not even exist.

This is, in my humble opinion, the most purely erotic piece in Klimt’s entire catalog (just beating out his assorted, highly sensual depictions of water maidens). He enjoyed baiting the people who chastised him for the sexuality he put on display; hence the use one of his favorite devices: the brazen, flowing red hair. The sleep/dream eroticism hinted at in The Kiss is in full effect here. And again, we have ornamentation, this time used to slightly humorous effect in its furtherance of Klimt’s emphasis on female sexuality. The round symbols on the cloth beneath Danae (likely taken directly from antiquity, although I couldn’t tell you which one; Greek would seem to be the obvious choice given the subject, but I can’t be sure) are obvious, but the male presence has become downright negligible, at least from a symbolic standpoint. Where the man was once resigned to merely turning his face from the viewer, he is now made of pure suggestion, including the one vestige of the male symbols that remains: a single, solitary black rectangle floating beneath the golden stream. Between Danae’s body, drawn up into itself, and the look of focused intensity on her face, one gets a sense that she is no longer even aware of the presence that is giving her such pleasure. Subsequently, the image becomes an expression of female sexual independence while still retaining the charge of male sexual fantasy of the story from which it was taken.

Next: The Faculty Paintings (1907)