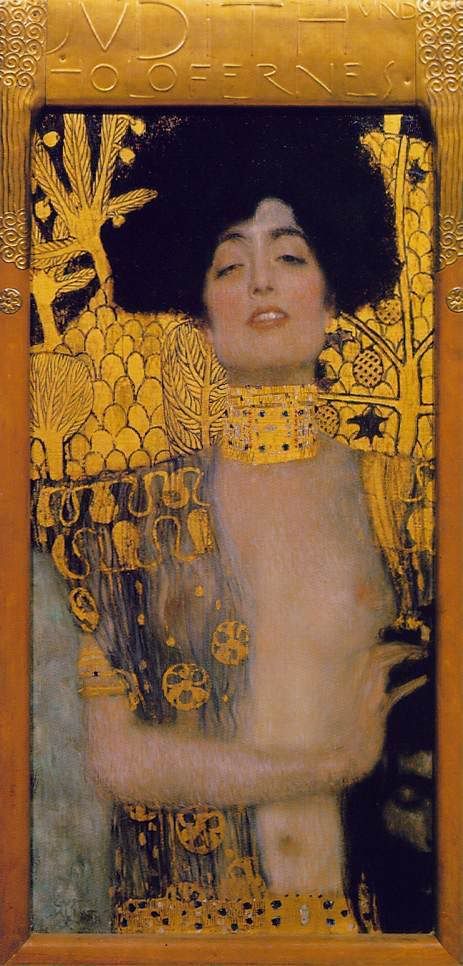

Judith I (1901)

Any artist who trucks in the transgressive could be forgiven for wondering what reaction a given piece of work might elicit (unless that’s the sole purpose for creating it, which I would say cheapens the artistic process, but let’s not go down that road for the moment). Will it be praised, jeered, banned, destroyed? All of these have happened to various works at various points in history, but Klimt’s Judith I is the only painting I am aware of in which a portion of the public reacted to the offense it caused them by pretending the subject was something other than what it was, right down to refusing to call it by its rightful name.

Judith I depicts the title heroine, a Jewish widow who snuck into the camp of Holofernes, an Assyrian general sent by Nebuchadnezzar to clamp down on the populace, seduced him and then lopped off his head. He chooses to present her in a contemporary context, as indicated by her fashionably Viennese clothing, the ornamentation of which blends in with the representative background, even bleediing out onto the frame. Once again, the male presence is muted; for starters, he’s just a head, but he’s also clasped down to her side near the bottom, half of his face cutoff by the edge of the picture. But that’s okay; it’s her face we need to be concerned with anyway.

Having decapitated a man, Judith doesn’t just seem peaceful, she seems positively, even defiantly serene. She proudly sports ornamental jewelry, is completely indifferent to her nude torso showing through her tunic, and with her eyes nearly shut, she gives us another depiction of Klimt’s persistent sleep/dream motif. It has been speculated that the picture is a (possibly unconscious) reaction to the growing influence of women in public life, indicated by the reversal at work in the fact that Judith used sex to lead a man to his demise, and yet is it she who seems aroused in the picture. She enjoys all of the power and all the pleasure as well.

The impudent empowerment angle alone might have been enough to raise eyebrows in a society, cultural renaissance notwithstanding, as repressive as the one in which Klimt lived, and if that didn’t, the juxtaposition of eroticism and violent murder might have done the trick. Add to that the fact that the subject is a revered Jewish heroine of the Old Testament and you’ve got all the ingredients for a public outcry. What is most interesting is the way the public, notably Vienna’s Jewish bourgeoisie, opted to react – namely that the artist must have made a mistake. This wanton vixen, with her languorous and lascivious expression, couldn’t possibly be the noble Judith of legend; clearly Klimt had intended to depict a different Biblical figure associated with decapitation, Salome, the young tart of a dancer who played the patsy in convincing her stepfather King Herod to take a little off the top of John the Baptist. So eager were they to believe this that they managed to create what we now call a meme, and the result was that numerous catalogs and journals for years afterward continually referred to the work as Salome. All this despite the fact that Klimt, as you’ll notice if you take another look at the painting, name-checked his subjects at the very top!

Judith II (1909)

Eight years later, Klimt would revisit the subject with notable differences. Judith is still unapologetic, defiant and bare-breasted, but instead of being clasped to her side, her hand resting in an almost gentle manner upon it, Holoferne’s head now dangles, his hair wrapped around her bony fingers. Gone is the suggestion of sexual pleasure to be replaced by a far more raptorial expression and stance.

I do not know if there was any correspondingly negative response to this work as there was to its predecessor. (If there was, not, in fact, an outcry over Judith II, it may say something, given their differences, about exactly how long the ‘violence=okay, sex=bad’ mentality has been floating around.) But then, by that time, having renounced governmental sponsorship after the rejection of the Faculty paintings, and making a nice living off of a steady stream of society portrait commissions, Klimt probably wouldn’t have cared one way or the other.

Next: ???

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home